“A sex offender wants to talk to you”; reporter’s journey leads her to Nebraskans Unafraid

Understanding sex offenders: the untold story

An inside look at the people on Nebraska's sex offender registry

READ MORE and WATCH VIDEO: http://www.ketv.com/article/understanding-sex-offenders-the-untold-story/13144523

OMAHA, Neb. —

“A sex offender wants to talk to you”

I’ve made people’s stories my life’s work. I’m a person who talks to people sitting next to me on airplanes. I engage people at grocery stores, and even while sitting in those flimsy robes in the hospital, waiting for a mammogram. I generally like people. And I constantly “interview” them, even when I’m not working. I consider myself open-minded. I’d rather ask questions than answer. I try not to judge.

But one fall day last year, a random call to the newsroom caught me off guard: A co-worker shouted across the newsroom that a sex offender wanted to talk to me. Everyone looked at me. My first inclination was to bolt. Not only did I not want to talk to a sex offender, I certainly didn’t want him to have my phone number or know my name. I was slightly unnerved.

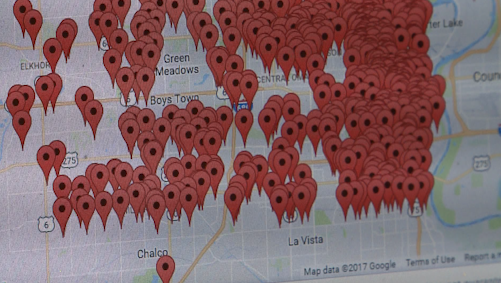

I’m calling him “Jay” and he’s part of a group trying to throw out Nebraska's sex offender registry or at least repeal a Nebraska law put in place seven years ago. The law essentially put anyone with any kind of sexual offense on the Nebraska Sex Offender Registry, an internet database, for all to see. Prior to 2010, only those offenders deemed most at risk to reoffend were on the list. And only law enforcement knew about the lower-risk offenders, so when the law changed, the list nearly doubled overnight. There are currently more than 5,200 people on Nebraska’s registry.

The registry includes child molesters and those caught peeing in the bushes, people who’ve accidentally downloaded child pornography in which a 19-year-old young man had a 15-year-old girlfriend. They’re now married with three children, but he’s on the public registry for life as a sex offender.

Jay was trying to get my attention, trying to share his story. So I did what a journalist does. I set aside my biases, choked down my fear and started talking to him. After his third call to the newsroom, about six months later, and the announcement that it was again the “sex offender,” it began to feel normal to chat with the guy, just as I chat with many other sources. Jay is polite and well-spoken. I could often hear a baby cooing in the background while we talked. Jay has sole custody of his 1-year-old daughter.

“I make sure she’s safe. She’s my number one priority, no matter what the situation is,” he told me about the squirmy, curly-haired girl.

Jay grew up in foster homes -- 32 of them, to be exact. He was a foster child for 15 years. He wasn’t seasoned at dating or meeting girls. He admits he had literally no relationship practice, and no role model. He’s 27 years old now and a few years ago, a friend introduced him to a dating app called PlentyofFish. He was lonely. He was looking for companionship. He met up with a woman through the app and they hit it off.

“I was 24, going on 25 and she said she was 19 and going to college, hair school. I had no reason not to believe what she said,” he told me.

The girl was 14 years old. And the hammer came down on Jay after she ran away from home and was found in his company.

“I take full responsibility for mistakes,” he said, “especially the ones I have control over."

He served a year in prison, but Jay said he’s now serving a life sentence on the sex offender registry. Last year, his girlfriend gave birth to a baby girl, and Jay became a father.

“She’s the reason I’m still in the fight, the reason I’m doing what I’m doing,” he said about his daughter.

As someone on the registry, he must check in with sheriff’s deputies every three months. They need to know his address at all times, and the car he’s driving. Random hate-filled people drive by his house and scream at him, or pass around degrading leaflets labeling him as a monster because he’s on the registry. Jobs are nearly impossible to keep because the term “sex offender” creates an enormous amount of fear and uncertainty. No one wants to hear the circumstances surrounding his conviction. The baby lives with Jay. There are no laws in Nebraska that restrict children in the home of a sex offender. And for that, Jay is eternally grateful.

“We are Third World citizens,” he told me. He worries his child will be bullied. He can’t take her to swim lessons at the Y. She’ll never be able to have sleepovers. He’ll be able to go into her school if he has a reason to be there. He can’t live near a park or school.

I’d always thought or heard, or perhaps made up the fact in my mind, that all sex offenders are uncontrolled, creepy weirdos who simply can’t stop offending. I thought it was just a matter of time before they committed another offense against a child. I assumed it was a psychiatric or psychological disorder and that they couldn’t change or be cured. I’ve learned, some indeed are sick.

I’ve covered the stories of sex assault survivors, survivors of incest and children who’ve been sexually molested over the span of my 30-year career. I’ve cried with them. I’ve seen their lives destroyed and manipulated by selfish, sick people. But it’s a rare event to hear about the “other side.” It’s a side no one wants to hear, probably because we’re afraid.

She studies sex offenders

“If sex offenders are the group we as society fear the most, shouldn’t we try to understand them?" asked Dr. Lisa Sample, a dynamic criminal justice professor at the University of Nebraska-Omaha and one of the foremost researchers of sex offenders in the nation.

So what about the repeat crime rate for sex offenders? How high is it? Random friends I asked guessed about 50 percent of sex offenders repeat their crimes.

“Actually, sex offenders have a lower rate of recidivism than any other violent crime type. The highest actually is robbery,” Sample said. She’s written briefs for the U.S. Supreme Court. She’s called as an expert by policymakers as they create and change laws to keep an eye on sex offenders. She’s a rare bird in a community of sociologists, someone who chooses to study the most loathed and misunderstood members of society.

95 percent will not commit another sex offense

Sample is petite, chatty and bold, with colorful, rock star hair and a powerful voice, who seems to speak a different language when it comes to sex offenders, because she’s taken the time to listen. Over the past five years, she’s continually interviewed more than 130 former sex offenders, welcoming them to her office on the UNO campus. She gathers their life histories to learn why they don’t reoffend. I’ve learned that they reoffend less than I thought. They reoffend less than most people think.

“What we’ve done for years is just look at the worst of the worst. The child sex offenders who rape and murder are very rare. That’s why it makes the news,” Sample said.

She points to a recent study by UNO colleagues that shows the number of sex offenders who repeat sex crimes after conviction rests at about 5 percent here in Nebraska, which means about 95 percent of folks on the registry will not repeat a sex crime. Another study published this spring -- with researchers from Johns Hopkins University and University of Wisconsin-Madison -- shows slightly higher rates nationwide. The study focused on 7,000 offenders. Overall, after five years, about 9 percent reoffended. The study is titled, "Once A Sex Offender, Not Always A Sex Offender."

So what makes sex offenders not reoffend?

“There are a lot of people who can have it really bad at one point in their life and, amazingly, humans change over time,” Sample Said. “We make decisions different today than when we were 18, and they (sex offenders) are no different.”

Sample’s personal interviews with former offenders led her to believe many sex offenses are an “episode” during a stressful time in their lives.

“A lot of people were in this situation at the time of their crime, where everything was awful -- their marriage, their job. They lacked intimacy. They were lonely. There can be a personality type that is more introverted and closed off,” said Sample.

It’s important to note that these factors are not excuses for offending. There’s no excuse for offending, ever. These are situations reported to Sample about people’s emotional state when they acted out on an innocent child.

Sample said positive social bonds help prevent sex offenders from reoffending. But, Sample said, many public sex offender registries tend to prevent and sever social bonds, by doing what some call “publicly shaming” offenders who’ve served time, attended therapy and shown genuine remorse for their crimes. All felons have a tough time finding jobs. Add a sex offense into the mix, and many end up homeless.

“All my time, looking for jobs, it’s been no, no, no,” said one former offender just out of prison after a five-year sentence. She spends her days applying for jobs and stopping at food pantries so she doesn’t starve. She said she is deeply remorseful for her crime, which happened 15 years ago. She’s attended therapy and apologized to her victim.

Sample listened, without judgement, to another study subject, as if she’d heard the story 100 times before.

I would learn a few weeks later, the woman was hired for a decent job in her field, a desk job that had nothing to do with children. But when the company did a background check, it rescinded the offer.

Sample believes not all sex offenders are alike. That’s why she’s on the state’s Justice Behavioral Health Committee, working to get assessment back into parole and probation so that all sex offenders won't be treated the same.

Sample said those who commit sex crimes against children 12 and younger, those who commit violent attacks on strangers and offenders who abuse both boys and girls are a special breed of sex offender and must have the highest level of surveillance. She said pedophiles have a high risk of reoffending because they groom children and view them as appropriate sex partners.

“They are the ones who definitely belong on the registry," she said. She believes Nebraska needs to go back to risk-based systems that allow for individuals to be assessed and assigned a risk level so that the lowest-risk offenders aren’t continually stigmatized and punished for a lifetime. In addition, Sample said, social connections lower the risk factors.

U.S. District Courts in two jurisdictions agree. A federal judge recently ruled Colorado’s sex offender registry is unfair to sex offenders, calling it cruel and unusual punishment. Another ruling said Michigan could not retroactively apply its sex offender law to people who were convicted before the state decided to put “all” offenders on the registry. Nebraska retroactively put offenders on the registry in 2011.

“I think it’s meant to be punitive. It’s there to protect,” said Amy Richardson, head of Omaha’s Women’s Center for Advancement. She said the registry serves the purpose of identifying people who put the community at risk, but she said everyone is lumped together. It’s not clear who’s a violent criminal.

Whom should we fear?

Crime experts told me we should be most concerned about people we know who are around our children all the time. Sample said the first-time sex offender who knows our children is more likely to grope, touch or sexually violate a child than a stranger on the sex offender registry who’s already gone through punishment and treatment.

A former offender with a church, friends and family is less likely to reoffend said Sample, because they have healthy connections and they’ve been punished. And this is alarming: one criminologist told me most child victims, 90 percent of them, know their abuser. Here’s the really sad part: Most of these cases go unreported. So really, the 5,200 on Nebraska’s registry are just a small fraction of those who’ve offended. The rest simply haven’t been caught.

Making healthy connections

It’s a Wednesday night, and a huge wooden table in a midtown Omaha dining room is set for a party. There are 12 places at the table.

Jay arrives with his baby. In the busy kitchen, beef roast and potatoes cook in the oven. A cheerful woman slices garden tomatoes on the counter and several gentlemen visit and make small talk. A lady with long dark hair is rolling up crescent rolls and Jay’s baby is taking down a bottle.

A man named Ken hosts this weekly dinner. As he places the pot roast on the table, they hold hands and pray.

“Dear Lord, we thank you for being so gracious that you would accept all of us in your presence,” and he continued.

Ken is a convicted sex offender, as are most of the visitors in his home. They call it “Wednesday dinner.” It’s part of the bonding they do in a support group called “Fearless” through an advocacy group known as Nebraskans Unafraid. The goal of the group is to abolish the sex offender registry, saying it discriminates and makes people the target of hate long after they’ve served their sentences. Nebraskans Unafraid

I ask them what they’re unafraid of. And then I realize, it’s me, and all of us on the outside who are afraid of them. Their goal is to inform us. It’s to show us they’ve changed. It’s to prove they are not the “monsters” they’ve been labeled since their arrests and convictions.

“The registry is designed for people just like me,” said Ken, who admitted that many years ago, he inappropriately touched his daughter’s friend.

Ken spends his days doing errands for sex offenders, volunteering at his church and running the family business.

“When we understand why we did something wrong and the hurt that we feel, that’s the biggest reason people like me would never reoffend,” he said.

Ken’s wife of 30 years was prepping dinner and I wondered, as many would, why did she stay with her husband who admitted, he did something awful to a child?

“We are all Christians and we realize that God has forgiven us,” Ellen said. She also told me she takes her marriage vows seriously.

Together, the couple rents out a small basement apartment for sex offenders who leave prison and have nowhere to go. They’ve hosted four men so far, each staying for a year, with permission from the state. Just one out of 100 sex offenders have a place and a person to return to when they get out of prison. Ken and Ellen take the former offenders under their wing, making them leave the house on outings, to go to church and the store.

“The biggest thing the folks at the prison told me is, ‘Don’t let them isolate,’” said Ellen.

This group is a connection to the outside world. It’s a place where they admit mistakes and talk about making amends. Sample said this group is one of the social connections that will keep them from being so isolated and from reoffending.

What about the victims?

An intriguing woman is seated at the table. She’s prayerful and cheery. Judith James tells me she too stayed in the couple’s apartment when she went through a divorce a few years ago. She reveals that she met Ken and Ellen in church and felt their home would be a place of healing for her. Judith has a unique perspective seated at the table of sex offenders. She tells me she’s an incest survivor, abused from age four up until the age of 13, and she recently forgave the offender.

“When I turned 13, I put the dresser up against the bedroom door. And when he tried to get in, I told him, ‘You touch me again, I’m going to tell Momma,’” James told those seated at the table.

James told the group, the sex offender registry wouldn’t have protected her. The man who often came to her bedroom door wasn’t on the registry. She said we are fooling ourselves if we think the registry keeps us safe.

James said it’s her role to minister to the group, by letting them know what it’s like to be a child victim.

“It’s about growth and watching people walk through life after they’ve done something horrendous and turn around and not do it anymore,” said James.

There are no judgements here. They are all “registered citizens” just trying to live a life where mistakes were made, children were deeply hurt, and those responsible seem to be making an honest attempt to try to heal and make amends. Each belongs to a church. Most have jobs or are looking for one. Some have spouses.

I’m one of a few new visitors on this night and at one point, someone asks what it’s like to be in a room full of felons. We laugh. But at this point, I’ve spent so many hours talking to them on the phone, interviewing them, getting answers to my questions that I forget they are felons, and I see them as humans, with their own story to tell.

What do advocates say about the registry?

She stopped to see me on her lunch hour from Creighton University where she helps adult minority students get into college. Leontyne Evans is 30 years old, confident and extremely self-aware of who she is and where she’s going.

“I am a victim of childhood sexual abuse. I’ve been a victim of molestation and sexual assault and I’ve forgiven those two people,” she tells me calmly and without hesitation.

Being a survivor, Evans has a valid opinion about the sex offender registry. But she has a deeper insight. She also worked for the state for a year, teaching classes to sex offenders before their release from prison. She left the program because she felt like it wasn’t challenging offenders to get to the root of their issues. None were encouraged to learn why they offended in the first place. The prison didn’t care what the root cause was, she said. Evans learned more than half of the men in her classes were sexually abused as children. She said it broke her heart to hear their stories.

Evans’ evening job is one of her passions. She’s a life coach, specializing in healthy relationships. She works with women who’ve been in abusive relationships or who’ve been sexually assaulted or molested. She uses Nebraska’s sex offender registry when women are in relationships and they want to check on an individual who they might want to date. She said the registry is broken, confusing and not user friendly.

“It’s not in laymen’s terms,” said Evans.

Each name on the registry is accompanied by a photo and a list of laws the person broke.

“Statute 12 point 389. We don’t know what that means,” laughed Evans.

The registry lists offenders by crime type, after a change about seven years ago, there are no “risk factors” to reoffend, associated with each person. Evans said the registry’s biggest flaw is that it’s not clear who’s dangerous and who’s not. The old registry labeled offenders as level one, two or three. And the ones least likely to reoffend were kept off the registry.

“Is it statutory rape or regular rape?” Evans said there’s no way of knowing the circumstances surrounding the crimes and that’s what makes the registry ineffective. She also personally knows people on the registry who are not dangerous.

“They went to a college party. She was 16. He was 21. Now he’s a lifetime offender,” Evans said.

She said if the registry is a tool to keep the community safe, it should be a useful tool.

“Let’s fix it. I just want to fix it. If we are going to use the sex offender registry as a free resource to the community, let’s enhance it,” she said.

Evans published a book this year called Princeton Pike Road, available on Amazon.com and in local bookstores. Her childhood home in Arkansas was on Princeton Pike Road. The book chronicles what it’s like to be a child molestation survivor. She wants sex offenders to read it. She wants other survivors to draw strength from it.

After our interview, the texts are piling up on her phone. They are the survivors, who need her help. But she said, sex offenders need help too. They need resources coming out of jail. They need jobs and support groups and therapy. And she said, we need to look around us, at those among us who are not on the registry and pay close attention to those who befriend our children.

“We can’t just keep casting stones and people think that’s going to fix it,” she said.

Resources

To report a child in immediate danger, call 911.

To report child abuse and neglect in Nebraska call: 1-800-652-1999, 24-hours a day.

To learn more about Leontyne Evans and personal coaching, visit: ExploreTheEvansExperience.com.

Nebraskans Unafraid is looking for quality, affordable housing for people they serve. To contact the group go to Nebraskans Unafraid

To join the group Fearless call 402-403-9250 or e-mail: nunafrd@gmail.com